Seventeen years after being the forefront of the New York Times’ plagiarism and fabrication scandal, Jayson Blair reflected, during a phone interview in Sept., on the paralyzing and vivid emotions that still have a stronghold on his mind: “It was like a f*cking panic attack,” he said. “I can still feel it to this day.”

Blair can still feel the trepidation caused by wrongdoing. He can still feel the titillation caused by the Big Apple. And, most profoundly, he can still feel the tumult of personal pressures circulating the Times newsroom, ones that couldn’t be edited from his story.

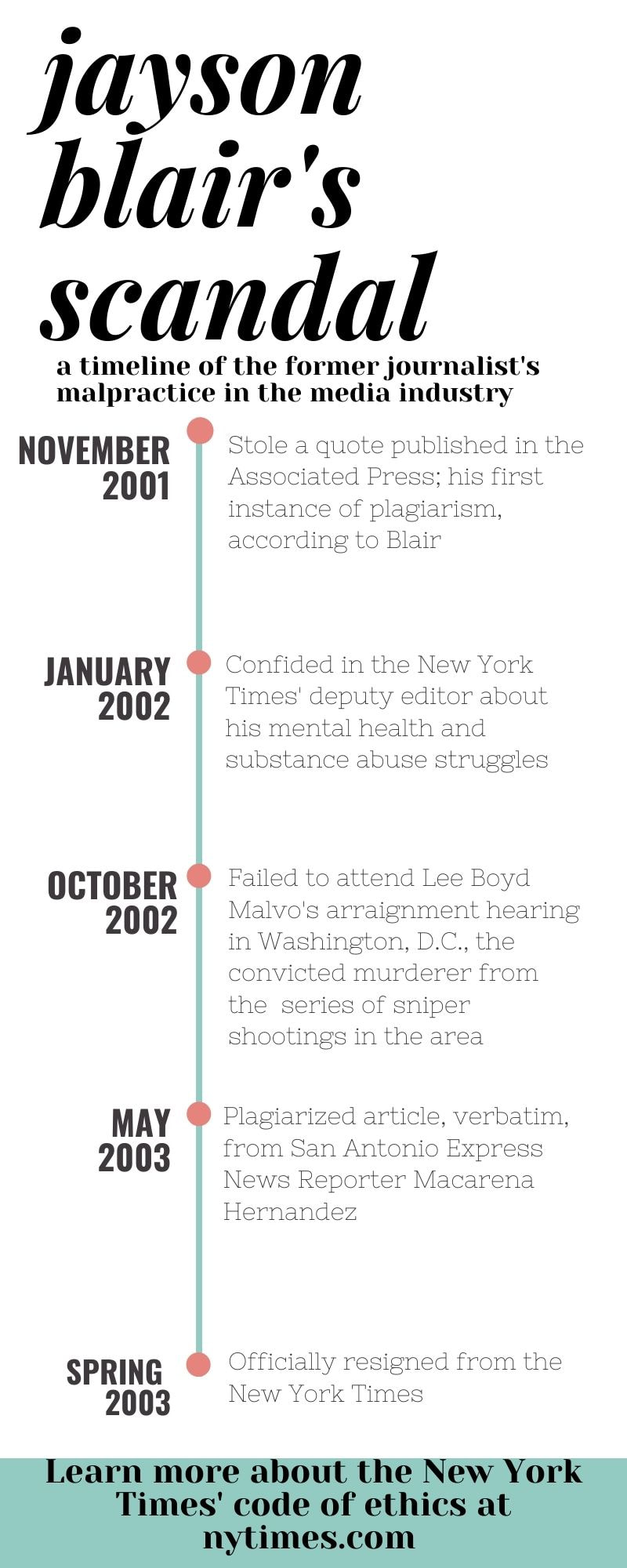

He explained his experience in a timeline: “First, was panic. Second, the New York Times called me in. Third, I lied and lied and lied, pretty well but clearly very charmingly because lawyers caught onto my lies and were still sympathetic. Fourth, I got suicidal. Fifth, it clicked in my head that this all wasn’t worth it, leading to my resignation in the spring of 2003.”

Blair was entwined in a feeble web of fabrication, plagiarism and unethical behavior, the Times describing his actions as “a low point in the 152-year history of the newspaper” in its lengthy disclaimer and investigation of Blair’s actions, “Correcting the Record.” The Times wrote “his tools of deceit were a cellphone and a laptop, which allowed him to blur his true whereabouts, as well as round-the-clock access to databases of news articles from which he stole.”

Blair, now a 44-year-old life coach based in Centreville, VA, is relatively open to discussing his time spent chasing (or not chasing) stories for the Times. After all, his was certainly not the only plagiarism scandal the journalism industry has seen. Janet Cooke from the Washington Post, Jay Forman of Slate Magazine and Jonah Lehrer with The New Yorker experienced similar repercussions as Blair for ethical misconduct. Yet, Blair’s complex weaving of undiagnosed bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety – what Blair describes as his “character deficits” – makes his case unmatched.

“I’m impulsive, and I was impulsive before my bipolar diagnosis,” Blair explained. “I often don’t think through decisions and I can also be highly manipulative – the worst version of creative thinking you can imagine. Now, these qualities of mine don’t always exist, but they tend to exist when I’m under stress.”

Alongside these character deficits is, surprisingly, a not-so competitive edge expressed by Blair. While describing himself as “highly competitive, intellectual and curious,” he interjected and said he wouldn’t call himself ‘highly’ competitive. Blair has an onion-layered definition for how competitiveness plays out in his personality and at work.

“My competitiveness displays in untraditional ways and I think that’s one of the misconceptions about me in general, was that this was all about fame or getting credit,” he explained. “I’m not a particularly anxious person so I don’t think I was striving to compete for competition’s sake or my ego, but I think I have a general self-confidence – I’m driven to accomplishment. It’s kind of tied to my identity in an internal way, the idea of running and gunning against the best journalists out there.”

Though Blair later described his overall Times experience as “fun, interesting and exhilarating,” he noted he was under enormous stress, debilitating him so much so that he failed to attend the arraignment hearing of Lee Boyd Malvo, the convicted murderer from the series of Oct. 2002 sniper shootings in Washington, D.C., Blair confirmed.

“Nobody asked me where I was,” he remembered. “You know how journalism is – it’s all about trust, right? So you’re out there, they know you’re out there, but I was literally 20 minutes west of the courthouse at my hotel.”

Ginny Whitehouse, Ph.D., Eastern Kentucky University journalism professor and media ethics researcher, believes the journalism system itself, not necessarily the individual journalist, is the root of many plagiarism cases such as Blair’s.

Blair can still feel the trepidation caused by wrongdoing. He can still feel the titillation caused by the Big Apple. And, most profoundly, he can still feel the tumult of personal pressures circulating the Times newsroom, ones that couldn’t be edited from his story.

He explained his experience in a timeline: “First, was panic. Second, the New York Times called me in. Third, I lied and lied and lied, pretty well but clearly very charmingly because lawyers caught onto my lies and were still sympathetic. Fourth, I got suicidal. Fifth, it clicked in my head that this all wasn’t worth it, leading to my resignation in the spring of 2003.”

Blair was entwined in a feeble web of fabrication, plagiarism and unethical behavior, the Times describing his actions as “a low point in the 152-year history of the newspaper” in its lengthy disclaimer and investigation of Blair’s actions, “Correcting the Record.” The Times wrote “his tools of deceit were a cellphone and a laptop, which allowed him to blur his true whereabouts, as well as round-the-clock access to databases of news articles from which he stole.”

Blair, now a 44-year-old life coach based in Centreville, VA, is relatively open to discussing his time spent chasing (or not chasing) stories for the Times. After all, his was certainly not the only plagiarism scandal the journalism industry has seen. Janet Cooke from the Washington Post, Jay Forman of Slate Magazine and Jonah Lehrer with The New Yorker experienced similar repercussions as Blair for ethical misconduct. Yet, Blair’s complex weaving of undiagnosed bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety – what Blair describes as his “character deficits” – makes his case unmatched.

“I’m impulsive, and I was impulsive before my bipolar diagnosis,” Blair explained. “I often don’t think through decisions and I can also be highly manipulative – the worst version of creative thinking you can imagine. Now, these qualities of mine don’t always exist, but they tend to exist when I’m under stress.”

Alongside these character deficits is, surprisingly, a not-so competitive edge expressed by Blair. While describing himself as “highly competitive, intellectual and curious,” he interjected and said he wouldn’t call himself ‘highly’ competitive. Blair has an onion-layered definition for how competitiveness plays out in his personality and at work.

“My competitiveness displays in untraditional ways and I think that’s one of the misconceptions about me in general, was that this was all about fame or getting credit,” he explained. “I’m not a particularly anxious person so I don’t think I was striving to compete for competition’s sake or my ego, but I think I have a general self-confidence – I’m driven to accomplishment. It’s kind of tied to my identity in an internal way, the idea of running and gunning against the best journalists out there.”

Though Blair later described his overall Times experience as “fun, interesting and exhilarating,” he noted he was under enormous stress, debilitating him so much so that he failed to attend the arraignment hearing of Lee Boyd Malvo, the convicted murderer from the series of Oct. 2002 sniper shootings in Washington, D.C., Blair confirmed.

“Nobody asked me where I was,” he remembered. “You know how journalism is – it’s all about trust, right? So you’re out there, they know you’re out there, but I was literally 20 minutes west of the courthouse at my hotel.”

Ginny Whitehouse, Ph.D., Eastern Kentucky University journalism professor and media ethics researcher, believes the journalism system itself, not necessarily the individual journalist, is the root of many plagiarism cases such as Blair’s.

|

“The mental health issue did not start with the plagiarism, the mental health issue started with a system that allowed things to get out of hand – where there weren’t enough checks on the writing and it was easier to call someone a Phenom and allow them to rise to unrealistic expectations,” she said in a phone interview.

Whitehouse added mental health issues always creep into cases like this. Though Blair’s was eventually diagnosed, she said that over time, lying will begin to affect the brain. Under incapacitating levels of stress, she said, a journalist will eventually crack and make poor decisions. And, that was exactly the case for Blair. “Anxiety can be paralyzing and I wouldn’t call it a decision not showing up, but rather an inability,” Blair said. “I thought I was going to get caught, which only made the anxiety worse. I was in constant fear of being caught, but not constant fear of going back and forth and thinking I should have done X, Y or Z.” And while it is presumed for Blair to have been scrutinized to the T, he mentioned that he never received constructive criticism – he merely was asked the status of his stories and how he was doing in the reporting process. Blair’s anxiety-ridden moments as a journalist still swim around his mind, clear as the ocean. His first plagiarism accusation, he mentioned, involved stealing a written account from Macarena Hernandez, a reporter for the San Antonio Express-News. Hernandez featured a Los Fresnos woman whose son was missing in Iraq and, though Blair delivered a verbatim copy to the editorial desk, the Times rolled back his accusations. Blair expressed over the phone that ‘accused’ is an “interesting word.” When I asked him what he meant, he told me some journalists at the time of the scandal were “out to get him,” failing to recognize that the first time he was ‘accused’ wasn’t the first time he plagiarized. Blair delivered this story over the phone, detailing the hard truth of his actions and exactly how he felt, without missing a beat: “I definitely remember the first story I did plagiarize, before December of 2001, before the plane crash in Rockaway [N.Y., in November], a couple of weeks before that. I told you I don’t have much anxiety but I remember getting this assignment one morning – we were working 18-to-20-hour days, literally not going home and staying at a hotel – to go to a ‘man on the street’ about business in New York. I froze. Now, I didn’t freeze in the newsroom. I went out to the Upper East Side and, while looking for businesspeople, I just froze on the corner. I went back to the newsroom, not knowing what the hell I was experiencing, and I took a quote from an Associated Press story. It was a very interesting sequence of events. To some extent, the freezing is an anxious reaction – I didn’t know what the f*ck pulling the quote and not giving attribution was, but I hit the button on sending the brief article and it went from there to the line editors (they call them at the Times ‘back field editors’), and then it goes to the copy desk. And it was on the copy desk, and I had this panicked reaction where I was like, ‘Oh sh*t, I should go tell them to add the attribution to the Associated Press.’ And then I didn’t, for some reason. But I was convinced – absolutely convinced – they would figure it out. And then they didn’t.” |

Blair recognizes that he is to blame for the scandal that penetrates most, if not all, media ethics books in America. A multitude of ethical transgressions unraveled shortly after his first accusation and, though they still are unforgettable, he views mental health as secondary to the root of the problem – that being pride.

“Under an enormous amount of stress with undiagnosed mental illness, I compensated by using some of my worst qualities – pride getting in the way of asking for help,” he said. “Maybe they would have put me on other assignments, maybe they would have told me to take time off.”

Pride prevented Blair from reaching out for help years before his first accusation. He won’t forget the day the heavy burdens of drug and alcohol addiction, psychological pressures and journalistic malpractice were lifted from his shoulders – Jan. 7, 2002.

“I went and told the deputy editor for the metro section [at the time], Susan Edgerly,” he said. “I had set up breakfast with her to ‘talk about my career’ and I just blurted out, ‘I have a drug problem.’ That was not my intent, that was not my plan, it just came out.”

Yet, Edgerly wasn’t the first person he told. He shared his struggles, only one hour before sharing eggs and bacon with Edgerly, with someone who was not a family member, a friend nor a colleague. Her name is Maria, a “down to earth” confidant, Blair described, who knew more about his life than his closest friends at the Times.

“She was the first person I told, and it was really interesting because she’s just a normal person opposed to a journalist,” he remembers. “I had not opened up to anyone. She was the morning bartender I visited on the way to the office.”

Blair failed to mention this light yet heavy detail over the phone. He shared it with the Oprah Winfrey Network in 2014, telling me that in 17 years “nobody’s caught that one,” not one interviewer asked him about Maria – the woman who poured himself a glass of courage, allowing him to taste the acrid emotions he was going through.

“When I was a kid, my pastor used to say, ‘You don’t decide where you’re going to stop for the car, and under what conditions you’ll stop for the car, [that’s] on the side of the road as you’re driving up to it because by the time you make a decision, you will have driven by,’” Blair said. “It’s not the moment that it happens – it’s before that.”

Timing is integral, relationships are influential and Blair’s entire story is a testament to how every person has a story of their own – even if it’s not written ethically or perfectly all the time.

“I realized over time that what scandal is really about is a loss of trust in an institution that matters,” he expressed. “My story was about a loss of faith in the institution of journalism, and the reason why I’m here, sharing my story, is to build back faith in that institution.”

“Under an enormous amount of stress with undiagnosed mental illness, I compensated by using some of my worst qualities – pride getting in the way of asking for help,” he said. “Maybe they would have put me on other assignments, maybe they would have told me to take time off.”

Pride prevented Blair from reaching out for help years before his first accusation. He won’t forget the day the heavy burdens of drug and alcohol addiction, psychological pressures and journalistic malpractice were lifted from his shoulders – Jan. 7, 2002.

“I went and told the deputy editor for the metro section [at the time], Susan Edgerly,” he said. “I had set up breakfast with her to ‘talk about my career’ and I just blurted out, ‘I have a drug problem.’ That was not my intent, that was not my plan, it just came out.”

Yet, Edgerly wasn’t the first person he told. He shared his struggles, only one hour before sharing eggs and bacon with Edgerly, with someone who was not a family member, a friend nor a colleague. Her name is Maria, a “down to earth” confidant, Blair described, who knew more about his life than his closest friends at the Times.

“She was the first person I told, and it was really interesting because she’s just a normal person opposed to a journalist,” he remembers. “I had not opened up to anyone. She was the morning bartender I visited on the way to the office.”

Blair failed to mention this light yet heavy detail over the phone. He shared it with the Oprah Winfrey Network in 2014, telling me that in 17 years “nobody’s caught that one,” not one interviewer asked him about Maria – the woman who poured himself a glass of courage, allowing him to taste the acrid emotions he was going through.

“When I was a kid, my pastor used to say, ‘You don’t decide where you’re going to stop for the car, and under what conditions you’ll stop for the car, [that’s] on the side of the road as you’re driving up to it because by the time you make a decision, you will have driven by,’” Blair said. “It’s not the moment that it happens – it’s before that.”

Timing is integral, relationships are influential and Blair’s entire story is a testament to how every person has a story of their own – even if it’s not written ethically or perfectly all the time.

“I realized over time that what scandal is really about is a loss of trust in an institution that matters,” he expressed. “My story was about a loss of faith in the institution of journalism, and the reason why I’m here, sharing my story, is to build back faith in that institution.”