Content Creator Abby Asselin has been uploading lifestyle videos to her YouTube channel of more than 90,000 subscribers, consistently staying up-to-date on social media and pop culture news to sustain her audience. But when the University of Alabama graduate contracted COVID-19, she quickly swapped lighthearted fashion news for vital health news as the top world news story became her reality.

“No one truly understands the significance of this virus until they’ve experienced the pain of it with symptoms or are close to someone who was severely affected by it or lost their life from it,” she said over email. “Gen Z is the most experienced with virtual communication, so harness those skills.”

As the pandemic rages on and health experts continue to be plagued by the perplexities of the novel coronavirus, high-level science and medical journalism is more important than ever. Yet, a growing number of Americans do not completely understand and trust the news media. In a self-designed survey, 80 percent of respondents said they don’t trust television news, with only 30 percent trusting COVID-19 coverage.

Victoria Castronovo, a junior marketing major at The College of New Jersey, grew up with FOX News always plastered on the television screen. As someone who frequently checks Twitter for news instead of watching live broadcast, she began to develop opinions of her own and is now skeptical of health care coverage in the U.S.

“Why are we not hearing about flu deaths this season?” she questioned in a phone interview. “Why are we not hearing about people with lung cancer? What about ALS deaths? I think COVID-19 deaths are being overstated in the wrong ways and other illnesses are being understated.”

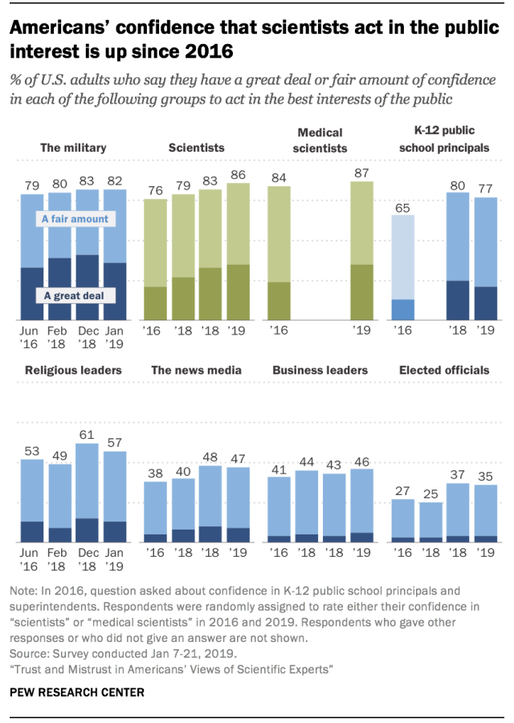

Castronovo is one of many who doesn’t have complete trust in the news media. In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, less than half (47 percent of Americans) believe journalists act in the best interests of the public.

“No one truly understands the significance of this virus until they’ve experienced the pain of it with symptoms or are close to someone who was severely affected by it or lost their life from it,” she said over email. “Gen Z is the most experienced with virtual communication, so harness those skills.”

As the pandemic rages on and health experts continue to be plagued by the perplexities of the novel coronavirus, high-level science and medical journalism is more important than ever. Yet, a growing number of Americans do not completely understand and trust the news media. In a self-designed survey, 80 percent of respondents said they don’t trust television news, with only 30 percent trusting COVID-19 coverage.

Victoria Castronovo, a junior marketing major at The College of New Jersey, grew up with FOX News always plastered on the television screen. As someone who frequently checks Twitter for news instead of watching live broadcast, she began to develop opinions of her own and is now skeptical of health care coverage in the U.S.

“Why are we not hearing about flu deaths this season?” she questioned in a phone interview. “Why are we not hearing about people with lung cancer? What about ALS deaths? I think COVID-19 deaths are being overstated in the wrong ways and other illnesses are being understated.”

Castronovo is one of many who doesn’t have complete trust in the news media. In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, less than half (47 percent of Americans) believe journalists act in the best interests of the public.

Ellie Kincaid, Medscape’s managing editor and graduate of New York University (NYU) Graduate School’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program, explains why she believes there isn’t a complete trust in American health care journalism.

“The average person might not have the awareness, especially with COVID-19, that the science is all very new,” she said during a phone interview. “One piece of research may say one thing and another piece may come along that may say the opposite. This can be confusing for readers and it just means that the science is still developing and there’s still a lot to learn.”

Ivan Oransky, MD, editorial vice president at Medscape and NYU adjunct associate professor, says COVID-19 coverage amplifies an issue that has been circulating the health journalism industry for years – information left for interpretation.

“What disappoints me about a lot of science and medical coverage, long before COVID-19 and probably long after, is the impression it leaves or the rush to report on single studies as if they were the last word, automatically meaningful just because they are published,” he said over the phone. “But I think there are a lot of outlets that have done a great job – questioning claims – and that’s what journalism should always be doing.”

Questioning claims is an essential for journalists, not limited to those reporting health care. Gina Escandon, Her Campus Media’s beauty and culture editor, is aware that the platform she works for features many college-aged journalists, many of which are first-time writers. In a time where credible news is especially important, she explains how Her Campus Media maintains a stronghold on accuracy.

“In addition to editing their work, my role also involves teaching them about how to source from experts, how to interview, and how to fact-check,” she explained via email. “I love to see how many medical experts, scientists, researchers, and even public relations representatives have made themselves more available to help journalists with COVID-19 coverage, and the relationship between writers and their sources has been amplified during this time because there’s such an urgency to get accurate and timely information out there.”

“The average person might not have the awareness, especially with COVID-19, that the science is all very new,” she said during a phone interview. “One piece of research may say one thing and another piece may come along that may say the opposite. This can be confusing for readers and it just means that the science is still developing and there’s still a lot to learn.”

Ivan Oransky, MD, editorial vice president at Medscape and NYU adjunct associate professor, says COVID-19 coverage amplifies an issue that has been circulating the health journalism industry for years – information left for interpretation.

“What disappoints me about a lot of science and medical coverage, long before COVID-19 and probably long after, is the impression it leaves or the rush to report on single studies as if they were the last word, automatically meaningful just because they are published,” he said over the phone. “But I think there are a lot of outlets that have done a great job – questioning claims – and that’s what journalism should always be doing.”

Questioning claims is an essential for journalists, not limited to those reporting health care. Gina Escandon, Her Campus Media’s beauty and culture editor, is aware that the platform she works for features many college-aged journalists, many of which are first-time writers. In a time where credible news is especially important, she explains how Her Campus Media maintains a stronghold on accuracy.

“In addition to editing their work, my role also involves teaching them about how to source from experts, how to interview, and how to fact-check,” she explained via email. “I love to see how many medical experts, scientists, researchers, and even public relations representatives have made themselves more available to help journalists with COVID-19 coverage, and the relationship between writers and their sources has been amplified during this time because there’s such an urgency to get accurate and timely information out there.”

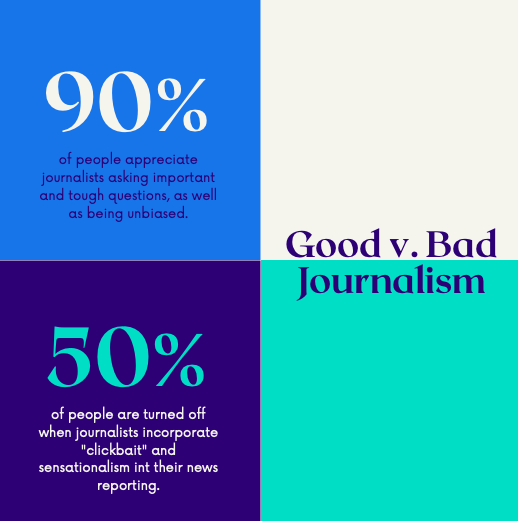

In the same self-designed survey, when asked what makes a good journalist, 90 percent of respondents said asking important and tough questions, along with being unbiased, are the two most critical characteristics. Fifty percent selected clickbait and sensationalizing the news, coupled with being biased, as the top two traits in a bad journalist’s DNA.

When reporting on health care, there are specific codes of ethics journalists keep in mind. Similar to how Americans should be intentional in deciding their news sources, Kincaid explains how journalists, too, must have both eyes open to where they extract their information.

“It’s especially important to think about whether a person who is being quoted – or the person who is speaking – has the expertise to talk about what they’re talking about,” she said. “Just because someone is a doctor doesn’t mean they have good information on COVID-19. Just because a paper in a journal says something doesn’t mean you should take it at face value.”

And, as some health-related news stories are buttered with sensationalized clichés like ‘breakthrough discovery’ and ‘holy grail drug,’ many news consumers read the headlines instead of the full story, drawing their own conclusions instead of seeking the truth, Kincaid adds. This has a snowball effect that builds on America’s vast and fractured media landscape.

Like Kincaid, FOX News health reporter Kayla Rivas also has a high regard for reporting medical news in an ethical way. At FOX, Rivas covers medical and scientific news, medical studies, and comments from officials at the Food and Drug Administration, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She explains the importance of sustaining credibility in her reporting.

“Health reporting is important for the public because it keeps them knowledgeable on best health practices, like studies on vaping are showing some lung injury,” Rivas said in an email interview. “I can safely assume the majority of the public does not sit and read through medical studies, so it’s important to break them down in an easily digestible form to inform the public.”

Oransky believes more Americans trust medical professionals rather than the news media, but that’s not to say there aren’t hidden health news gems within digital, print, and broadcast alcoves. In the same Pew Research Center survey, roughly 87 percent of Americans trust scientists and medical experts’ claims. Oransky explains the importance of collaborating with a team of other medical experts at Medscape to produce factual content.

“Everything from our reference material, which is written by the top experts in whatever the condition or specialty is, is reviewed by other experts, so there are a couple layers [in the news gathering process],” he said. “We link to all our sources, cite all the relevant literature, and do careful searches before that.” Oransky added that ‘perspective pieces’ are integrated into the platform, an opportunity for medical experts to offer their opinion on various topics – and yes, these are still reviewed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, Associate Professor at Yale School of Medicine and Medscape contributor, explained in a video interview how health journalism, at times, can be a slippery slope despite his ample education and experience in the medical field.

“I’ve been attacked on social media for doing some medical journalism but I’ve also been lauded for it and people have reached out to me and thanked me for my efforts,” he said. “People have been trained to reject facts that don’t comport with their own opinions and it’s only accelerated recently, and science journalists get caught in the middle of that.” Wilson added this can lead to Americans’ distrust of journalism, at times, as bias frequently rears its ugly head.

“Being a journalist in a time of COVID-19 is like trying to hit a moving target, in a way,” Kincaid explained. “It’s important for people to have access to true information about their health and what can affect it and unfortunately, there’s a lot of bad information out there so providing good information is an important service.”

Kincaid added that some Americans are unaware journalists who specialize in health and medical reporting exist. To combat American distrust in the health news sphere, the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) created its ‘Covering COVID-19 Handbook for Journalists,’ outlining how to fact-check for medical misinformation to ‘convey news in a manner that is appropriate, accurate, sensitive and palatable.’

American perception of health journalism is not a transparent picture. Because COVID-19 is ingrained in both personal and professional circles for a health care journalist, Oransky believes top priority lies in self-care for themselves and others.

“It’s an intense time for everyone and when your job is reporting what’s happening, that’s a tough place to be,” he noted. “This time is a health and science journalist’s version of going to war – even though bullets aren’t flying and we’re not being threatened by explosives, we are at risk of this disease.”

This is the COVID-19 era, a turning point in health care that will soon be trademarked in history books for the next generation. This time has completely restructured the way in which news is delivered and exchanged – truly a pandemic of public perception.

“My hope is that, if anything, the COVID-19 epidemic has crystallized in people’s minds the need for solid health journalism,” Wilson concludes. “And now, we have to teach them how to recognize it.”

When reporting on health care, there are specific codes of ethics journalists keep in mind. Similar to how Americans should be intentional in deciding their news sources, Kincaid explains how journalists, too, must have both eyes open to where they extract their information.

“It’s especially important to think about whether a person who is being quoted – or the person who is speaking – has the expertise to talk about what they’re talking about,” she said. “Just because someone is a doctor doesn’t mean they have good information on COVID-19. Just because a paper in a journal says something doesn’t mean you should take it at face value.”

And, as some health-related news stories are buttered with sensationalized clichés like ‘breakthrough discovery’ and ‘holy grail drug,’ many news consumers read the headlines instead of the full story, drawing their own conclusions instead of seeking the truth, Kincaid adds. This has a snowball effect that builds on America’s vast and fractured media landscape.

Like Kincaid, FOX News health reporter Kayla Rivas also has a high regard for reporting medical news in an ethical way. At FOX, Rivas covers medical and scientific news, medical studies, and comments from officials at the Food and Drug Administration, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She explains the importance of sustaining credibility in her reporting.

“Health reporting is important for the public because it keeps them knowledgeable on best health practices, like studies on vaping are showing some lung injury,” Rivas said in an email interview. “I can safely assume the majority of the public does not sit and read through medical studies, so it’s important to break them down in an easily digestible form to inform the public.”

Oransky believes more Americans trust medical professionals rather than the news media, but that’s not to say there aren’t hidden health news gems within digital, print, and broadcast alcoves. In the same Pew Research Center survey, roughly 87 percent of Americans trust scientists and medical experts’ claims. Oransky explains the importance of collaborating with a team of other medical experts at Medscape to produce factual content.

“Everything from our reference material, which is written by the top experts in whatever the condition or specialty is, is reviewed by other experts, so there are a couple layers [in the news gathering process],” he said. “We link to all our sources, cite all the relevant literature, and do careful searches before that.” Oransky added that ‘perspective pieces’ are integrated into the platform, an opportunity for medical experts to offer their opinion on various topics – and yes, these are still reviewed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, Associate Professor at Yale School of Medicine and Medscape contributor, explained in a video interview how health journalism, at times, can be a slippery slope despite his ample education and experience in the medical field.

“I’ve been attacked on social media for doing some medical journalism but I’ve also been lauded for it and people have reached out to me and thanked me for my efforts,” he said. “People have been trained to reject facts that don’t comport with their own opinions and it’s only accelerated recently, and science journalists get caught in the middle of that.” Wilson added this can lead to Americans’ distrust of journalism, at times, as bias frequently rears its ugly head.

“Being a journalist in a time of COVID-19 is like trying to hit a moving target, in a way,” Kincaid explained. “It’s important for people to have access to true information about their health and what can affect it and unfortunately, there’s a lot of bad information out there so providing good information is an important service.”

Kincaid added that some Americans are unaware journalists who specialize in health and medical reporting exist. To combat American distrust in the health news sphere, the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) created its ‘Covering COVID-19 Handbook for Journalists,’ outlining how to fact-check for medical misinformation to ‘convey news in a manner that is appropriate, accurate, sensitive and palatable.’

American perception of health journalism is not a transparent picture. Because COVID-19 is ingrained in both personal and professional circles for a health care journalist, Oransky believes top priority lies in self-care for themselves and others.

“It’s an intense time for everyone and when your job is reporting what’s happening, that’s a tough place to be,” he noted. “This time is a health and science journalist’s version of going to war – even though bullets aren’t flying and we’re not being threatened by explosives, we are at risk of this disease.”

This is the COVID-19 era, a turning point in health care that will soon be trademarked in history books for the next generation. This time has completely restructured the way in which news is delivered and exchanged – truly a pandemic of public perception.

“My hope is that, if anything, the COVID-19 epidemic has crystallized in people’s minds the need for solid health journalism,” Wilson concludes. “And now, we have to teach them how to recognize it.”